The Bureau of Suspended Objects in Jenny Odell's studio at Recology.

Recently, The Contemporary Jewish Museum (CJM) made the trek out to the San Francisco dump (for art’s sake of course). At the Recology Artist in Residence (AiR) Program, we chatted with artist, archivist, and internet (and now dump) miner Jenny Odell about her AiR project—The Bureau of Suspended Objects, the line between utility and trash, and how this experience might influence future projects.

And, in case you’re left wondering what’s next for Odell, she's participating in The CJM's ongoing installation series, In That Case: Havruta in Contemporary Art, collaborating with window dresser Philip Buscemi.

Tell us about the Recology Artist in Residence Program and the project you’re currently working on.

We’re at Recology, which is the recycling, waste, and compost facility for San Francisco. And they have had an artist-in-residency program for 25 years, with two artists at a time, for three months, between three and four months. I am currently one of the Artists in Residence, and I’m using my studio space and access to the public disposal area to create an archive of discarded objects. The public disposal area is not where the garbage trucks come in, it’s where the customers come in—people who might be getting rid of construction debris, who have to move in a really big hurry, someone [they know has] passed away, or just changing circumstances lead to people coming into this building and dumping things into a very huge pile, which is then processed. So, we’re kind of in there as it’s being processed; it’s pretty chaotic.

I’m going in there with a shopping cart, taking things—although I’m not anymore. I had to cut myself off. I’m bringing them back here, photographing them from multiple angles, cutting out those photographs, and from each items, creating what was a Tumblr post up until now, but will now be in a book. I look at what the object is, where it was made, and the company who made it—gathering background on the object. Asking, why does it exist? Who’s responsible for it? Does that company still make that object? And, I like to include TV commercials or any other kind of ad. Any details that give a sense of the physical sense of where it came from—so if I can say it was made in a three story building surrounded by palm trees in Thailand next to a river—to make it seem like a real place to people, not just this abstract. Because when you hear “Made in China,” it sounds like some mystery land. But it’s not; it’s a place. I’m trying to demystify it for myself as well.

So the archive is a Tumblr for now, and it’s going to be a book. There are 200 items in the archive. The archive exists here physically with these cards, and the cards have QR codes that lead to the website, so it also exists digitally. And it will exist in the book—and the photographic prints.

The Bureau of Suspended Objects in Jenny Odell's studio at Recology.

Do you find yourself looking at objects when you’re shopping, and being hyper aware?

Yeah! So I haven’t bought anything except for food and gas this entire summer. Because I can’t do it. Also, I’m convinced anything I need is already in the pile. Like the Apple mouse and wireless keyboard that I found that on day two. Except, when I plugged it in, it said “Laura’s mouse.” It’s really creepy. I feel like a lot of the electronics in here are haunted. (Laughs.)

I had to go to Office Max to get map pins, which I didn’t end up using. And a place like Office Max is just like shelves of trash. Now the store has started to look like the dump to me, and the dump to look like the store. It’s all the same: it’s just objects and material invested and divested with meaning, and then re-invested with meaning and then divested with meaning. The fact that something is trash only until I pick it up with my hands is strange. There have been really weird instances where I go in and I pick something up and suddenly it's not trash anymore. But, I’m still in there, a half an hour later, and I think, “No, I don’t have enough space in there for that.” So I put it back down, and it’s trash again. And I feel bad! I feel guilty for throwing it away, but it was already thrown away. So it’s all just about decisions.

People then come in here asking if I’m going to sell them, like it seems wrong not to sell these.

Right. But then it’s so much value put back on this object that was trash, until you invested it with meaning.

And, what’s also interesting to me too is that objects are really multifaceted; they have many possible meanings. One metaphor for it is like you find a lot of electronics that are missing adaptors or power supplies, so you can’t use it. It’s a perfectly well-functioning thing, but it’s kind of illegible because it’s missing its translator, which is the adaptor. So there are a lot of objects that I don’t understand the value of, but then someone will come in here and say, “Oh this is the blank that made blank that did blank.” There was a lather machine in here, and I had no idea what it was. I think it was from the 1940s, it’s Oster®, a blender brand, and I had to look really hard to find out what that was. But a barber would look at that and immediately know. In fact, barbers pay a lot of money for it. So, if you don’t possess the right filter, then a lot of things can be trash. But if you have the right filter for every single thing. . .I wish there was a way to design like a universal adapter for objects, just as a conceptual device, that you could use to understand and use any object—because the object still has usefulness and value inherent to it.

Yeah, it does.

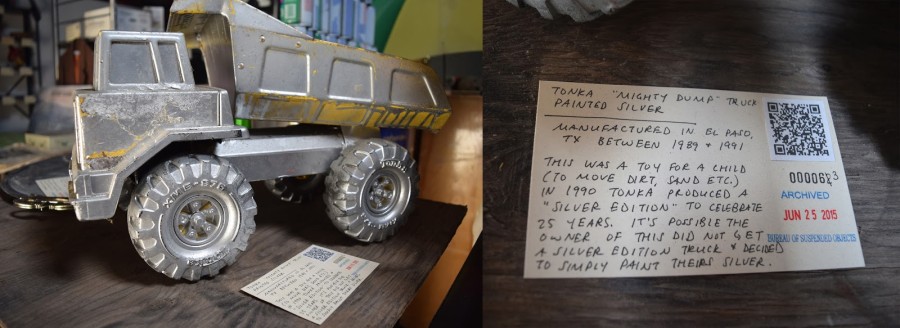

Can you talk about your two favorite objects?

Oooh. That’s so hard. Okay, I’ll just pick two of them. I really like the silver Tonka truck because, it’s a good example of the ways that I have just relied on people on the Internet just being fanatics about certain things. And I hope to be that person for other people in the future. So I have this Tonka truck, and it’s clearly painted silver by the owner, which makes it hard to date because the decals are covered up by paint. So I found this website, it’s just some guy, who’s really obsessed with Tonka trucks (actually a lot of people are), and he breaks down year by year every single design change in every single Tonka truck. Every year up to when they started being made in China, because after that, he doesn’t care, which I think is sometime late in the nineties. So I was looking very closely at these and I was actually able to figure out just from the wheel nuts on there, that it was made in 1990s...because it couldn’t have been made before nor after, so it was 1990. And then, I noticed that 1990 was the 25th anniversary of Tonka, so they made a silver edition, for which they made a silver addition. This was not that.

Ohhh!

So somebody was thinking, “I didn’t get the silver edition,” and painted it silver. Either for themselves or for their child. Which is like—

Maybe for the child.

I will never know! But it was so satisfying to find out why it was silver.

Tonka "Mighty Dump" Truck Painted Silver.

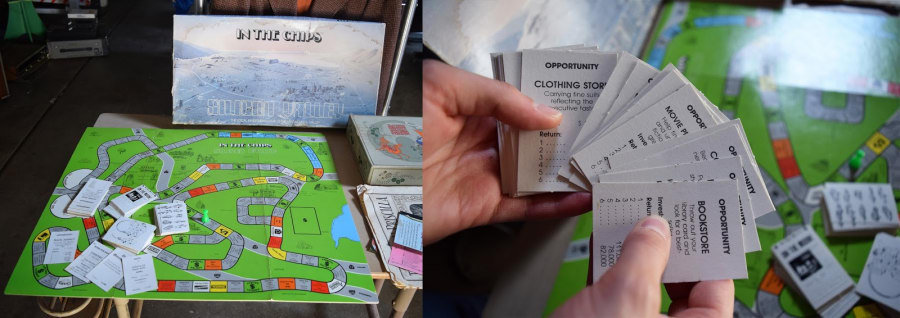

And then my other favorite thing is the 1980 Silicon Valley board game, which I actually didn't find myself; it was found by somebody who works here, the box was just lying around. There are a lot of interesting things just lying around here; and these things that people, other artists or people who work here, find and then have given them to me. I’m called The Research Lady—so they’re like, "Give it to Jenny, she’ll figure it out." They brought me this game, not knowing that I grew up here, so it has special value to me. My mom worked at HP and my dad worked at a tech company. My childhood mall is on that board, it’s really surreal. I really enjoyed going through those cards, where start-up means like starting a dry-cleaning business or a travel agency. It’s a really innocent version of Silicon Valley; people valorized Apple at the time, but the dot-com bubble hadn't happened yet, so it’s inadvertently a specific portrait of a specific time in a specific place.

It was designed by a guy who went to high school with "The Steves"—so Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs—and he went to high school with them but didn’t know them, but he met them at a photo shop in Cupertino—and I think I know the photo shop—and he did some early product photography for them. And I guess, he was just really inspired in general by tech people.

Fascinating.

So he designed the game and it was manufactured at the Box Factory, which is in South San Francisco and used to make paper and cardboard products. There’s no information at all about the Box Factory, except that they sued the city of South San Francisco because one year the Colma Creek overflowed and destroyed their entire paper stock. . .so they’re gone now. The building is now a handmade cosmetics company and the owner lives there, who seems a little wacky.

The found game about Silicon Valley, In the Chips.

So all of this you learned from Googling?

Well, it’s Google that leads to other things that are legitimate archiving; the Wayback Machine has been really useful too, especially for the way companies try to change product branding quietly without announcing it.

I have that roller skate over there—a Reebok skate that's branded RBK, which is the Reebok line. You can still buy those, but you’ll notice you’re buying them from like Amazon and not the official Reebok website. So, if you click on In Line skates on the Reebok site, it goes to CCM, which is a brand that they bought that is more recognizable to people who care about skates. But if you go back to earlier this year on the Way Back Machine, it goes to the Reebok skate. For things like that, you need the internet archives to be able to trace, because the companies are not going to tell you. I also worked at a corporation; I know how that works.

How did you get attached to some of these objects? I think that’s really interesting…

Yeah, I think that the act of slowing down and really looking and reading all the text on something, and spending lots of time figuring out why this is here. When you're in the pile, you're supposed to be quick. I’m that person who’s looking at everything just like an alien from out of space and wondering, “What is this?” That feeling is what I’m trying to foster in viewers toward objects they encounter or own. The logical conclusion of that is that you would probably throw things away less, and you would have a better understanding and appreciation of the systems that brought these objects to you. It’s not just the toothbrush you’re going to throw away, it’s some kind of material that was maybe injection molded and it was designed by somebody with a computer, and it’s going to go somewhere after you’re done using it. That explains this close attachment to things. Especially at this point because I’ve gone back over things several times—this is an unintended thing that happened—because I make the cards later.

So, the first pass is the Tumblr, then it’s the card, now it’s the book—and then I talk to people about the objects I archived. So I keep going over and over these things and I’ve memorized them in this way. I feel very full having these things because they have so much meaning—

Well they have a new meaning for you.

Yeah, but also, someone was saying—I don’t remember who—that it’s really poignant that these objects that were thrown away are getting their last glamour shot; their last moment of consideration. There’s something really funny and sad about the whole project: these orphaned objects that no one cared about and then intensely really caring about them for a period of time.

It also makes you think of the readymade works of art—they used to be functional or decorative objects, but now that half of it is missing or that they're not functional or they’re not beautiful, they have a new function. It feels like kind of a new kind of readymade.

Yeah, one funny example of that is that I have an Apple Powerbook G4 from 2002 that was made during the couple of years when they were made out of titanium. And it was unveiled at MacWorld 2001, and so Steve Jobs is drawing out this long thing, like “What do you think it’s made out of. . .maybe it’s titanium!” And then he goes on and on about titanium, that spy planes are made out of it, that it’s super long lasting and doesn't break. There’s something really funny about talking about the long lasting materiality of a product that’s supposed be old tomorrow. The irony being that it did last a long time—it’s broken in half but it’s still there and not going anywhere! So, the materiality of things is party of it; when you see the front loader in the pile trying to smash this mass of objects and see the resistance of things, it's amazing. That glass lamp over there… I saw it get smashed and it was fine; it just stayed the same.

Whoa!

The resilient Ore International Glass Lamp.

And some things aren’t resistant, some things are trashed. But even then, it’s just in more pieces now, it didn’t go away. That’s just kind of one of the realizations you have when you are in the pile, that these products are material fallout of someone’s ideas. Someone had an idea and fabricated it, and now it will never go away.

It’s interesting the range of age and objects in your collection, can you talk about that?

One important thing about this archive is that I was trying to get a good balance of objects. Overall, I wanted it to be a good portrait of our stuff—meaning really old versus really new; lots of information versus no information; really obviously cool versus not obviously cool; different purposes, like clothing and electronics. There’s a bank ledger from 1906 and a My Little Pony from 2014, and everything in between. So that got easier as I went along—the beginning seemed really arbitrary as I wanted to take everything with me, but as I went along, I started to fill in the spaces. Near the end, I realized I needed to get more things from this particular decade, or that I didn't have enough things made in Mexico or somewhere else.

Tell us about the GIFs that you are creating for the website, and the GIFs' relation to the physical objects.

Oh! The GIFs will be part of the show—I’m trying to make animated GIFs for as many objects as possible. They are supposed to have me in them somehow, with my hand using the object—some of them are obvious, like you see me playing the NES; but other things, like the smashed CD drive, it's a litter harder to think of something. Once I started making them, I realized that their appeal was that there’s something kind of undead about a GIF. It’s sort of alive…it’s not a movie and it’s not a photo. It just loops forever. There’s something about that that seems very similar to the way these objects are: where they are continuing to exist forever, with no actual endpoint or purpose. There’s something that I really like about seeing them—especially a grid of them—as briefly reanimated objects.

Kind of Frankenstein-esque.

Exactly, I like that effect. Oh and the other thing I should mention… I think it’s telling that the things I forgot to archive, that I didn’t get to before I hit the 200-object cap, were things that I ended up actually using. Like these shoes… I never archived them because I was wearing them the whole time; or I never archived my mouse because I was using it. That's just how we normally interact with objects: when they’re useful to you, they are transparent; and when they’re not useful to you, they become opaque and you want to get rid of them. They don’t fit into your system anymore. I remember that [Martin] Heidegger had this idea about the broken tool: that the tool is invisible until it breaks—that’s exactly what’s happening here.

Odell using her app to fill in the missing part of the found photo.

Can you talk about the app you have been designing related to the project?

One of the things I’m interested in with this project besides the function of time and value, is also the idea of a part of the whole. A lot of things in here are parts that are missing other parts, and so in order to understand an object on its own terms is to understand what it was supposed to be as a whole. The vintage photo panel is a real example, as it’s missing its other half. I wanted to see the whole thing, so the app lets you scan an image, and some flat things too, to either see the rest of it, or to see the original product photo digitally overlaid on it. It’s about time, and part and whole—using the object as the starting point to get other information that’s layered on top of it.

Did you ever think about the past owner of these objects you collected in your archive?

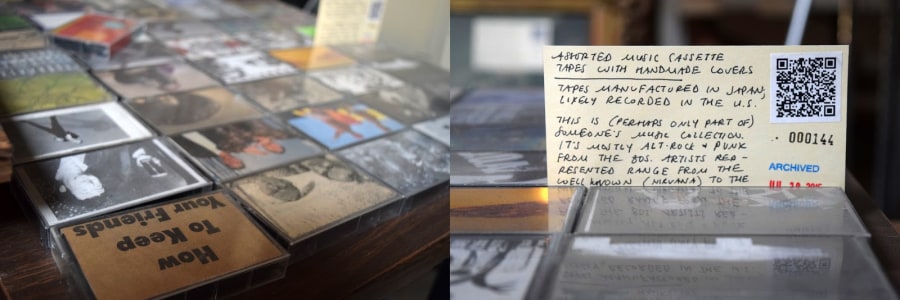

Not really, because I was so object-oriented. But, it happened for that tape collection over there with the personalized tape covers. . .because someone made it; it was that person's music collection. I feel like I understand that person—and as I was archiving that, I was listening to all the albums that are on that tape—I feel like I could know that person or hang out with them.

I think one of the reasons that I haven’t been so focused on the object's original owners is because I’ve put all of my resources into the beginning of the object story, and not really the end. The beginning part, its production, is the part that gets overlooked more.

One of my favorite YouTube videos is called Inside a Sony Factory, and it has so many down votes, because people think it’s an exposé and they click on it. It’s actually a camcorder that someone hit the recall button on and it was turned on in the factory. So it’s a stationary video of a Sony factory in Japan with people walking by and cameras being fabricated. You can hear people speaking in several Asian languages. I LOVE that video, it’s candid. The camera had a life before you bought it; that’s the part that gets forgotten—after you throw it away.

Tell us about your upcoming exhibition at The CJM.

I will be doing a series of window-like displays with Philip Buscemi, a designer and window dresser based in San Francisco, at The Museum. I will use objects from here, objects that are currently being used—either mine or borrowed from other people, and then new objects that are going to be returned after the show. They will all be arranged in a similar manner, in an appealing way—that’s what visual merchandising does. What’s happening here is that people are taking value out of things by throwing things away, but visual merchandising puts value into things. I know that because I worked with visual merchandisers at Gap—so I would see them take, not exactly raw material, but a box of shirts and making it into a thing that you would buy. I want to extend the feeling that I’ve had here to the viewer, who should ideally experience all of the objects as somewhat similar. The arbitrariness of investing and not investing value should hopefully become apparent.

Hopefully, there are two possible conclusions from that: everything has no meaning and is worthless; or, everything is incredibly meaningful. I think it’s one or the other and people are selective about it based on the circumstances. It’s the logical conclusion of thinking about materially. You think about the process of creating just material, such as through mining or growing cotton, and how that material is configured temporarily into something with value.

Assorted music cassette tapes with handmade covers.

_______________________

Jenny Odell's upcoming exhibition In That Case: Havruta in Contemporary Art will be on view January 26-Jun 26, 2016. Odell and collaborator Philip Buscemi will use the havruta case as an investigation into the different values associated with manufactured objects and their commercial display.

Jenny Odell is a Bay Area native/captive with an MFA in Design from the San Francisco Art Institute and a BA in English Literature from UC Berkeley. Her work makes use of secondhand imagery and vernacular online sources in an attempt to highlight the material dimension of our modern networked existence. Because her practice exists at the intersection of research and aesthetics, she has often been compared to a natural scientist. Her work has made its way into the Google Headquarters, Les Rencontres D'Arles, Arts Santa Monica, Fotomuseum Antwerpen, La Gaîté lyrique (Paris), the Made in NY Media Center, Apexart (NY), and East Wing (Dubai). It's also turned up in TIME Magazine's LightBox, The Atlantic, The Economist, WIRED, the NPR Picture Show, and a couple of Gestalten books. Odell teaches at Stanford University.

Pierre-François Galpin is Assistant Curator at The CJM, currently working on upcoming In That Case: Havruta in Contemporary Art exhibitions. Prior, he worked at the Centre Pompidou (Paris) and Independent Curators International (New York), among other institutions. His writing has been published on different media, including The Exhibitionist, Art Practical, and exhibitions catalogues.

Stephanie Smith creates online media and content as the Digital Engagement Associate at The CJM. She's an artist and designer, who co-founded smith|allen studio.

For more blog entries, click below.

In That Case: Havruta in Contemporary Art is organized by The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

Major support for The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibitions and Jewish Peoplehood Programs comes from the Koret Foundation.