We are delighted to share a glimpse into King’s studio work, her influences, and her work-in-progress, Diasporic Futurism: Taking Up (Outer) Space. The following is a recent conversation between Leah King and LaFrae Sci.

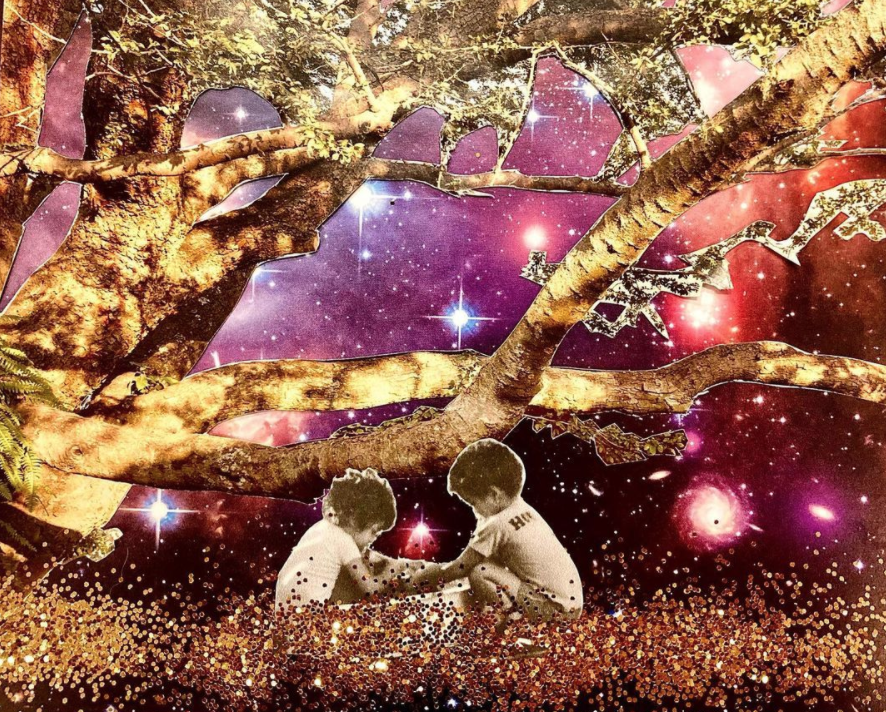

Leah King, Ava, Mixed media, 2021

Leah King, Ava, Mixed media, 2021

Leah: LaFrae, thank you so much for talking with me about art and futurism today. I thought it would be great for us to have this conversation because we've worked in parallel creative contexts for nearly fifteen years. I feel like we are constant collaborators, and even though we don't necessarily work on the same projects at the same time, there's almost an esoteric or ethereal—dare I say—spirit connection with the work we make. I think this comes from our connections to future visioning and Afrofuturism. Why do you think this work is so consistent for us, rather than time-based?

LaFrae: Well, time is a construct, right?

Leah: Yeah.

LaFrae: We got that out of the way real quick. For me, futurism helps me make sense of the places that my soul knows existed in the past, the present, and the future. Historically, for my lineage, that is not written down or known, for sure.

Leah: Right. This is a huge part of the project I'm working on, Diasporic Futurism: Taking Up (Outer) Space. How do I create an artistic representation of something that I've never spoken about, that I can only feel? There is a lot of language and construct around ancestral trauma, storytelling, and family. I’m trying to turn that into something creative. Where do we even start?

LaFrae: Where your feet are.

Leah: Yeah.

LaFrae: I mean, it starts where your feet are. For me, I had a very close relationship with my grandmother. She was the grio, the keeper of the stories. I grew up on a southern porch, surmounting the kind of situation where my grandmother would sit with a cigarette and tell the stories. I got a glimpse of certain things. She was always really great at remembering people; both their magic and their faults. She painted pictures in her stories. They made me proud of my past.

In contrast, I went to white schools for elementary school and the original TV series, Roots, dropped when I was in third grade. Everyone was watching it and nobody had the context to process it, not the white kids and certainly not me as a Black child. The images—the cruelty and the trauma that was presented and attached to Blackness—made me feel ashamed and embarrassed. When I got older and started finding ways to look at my life and my lineage through the futuristic side, I was able to see the brilliance, the timelessness and the majesticness. How about you?

Leah: I haven't seen Roots, but my parents talked about it a lot. As we know, very little African-American history is taught in public schools. Like you, I didn't grow up with the internet. I didn't have a phone in my pocket to research. I had to seek out those stories myself because I knew that they weren't being covered in the history books. An entire aspect of my heritage, my ancestry, my lineage, the facts of what had happened to us, were all hidden. My parents had spoken to me about the social and political construct of race since I was born, but as you were saying, the visceral experience of trauma on Black bodies—I didn't feel it as much in my loins when discussing with my parents as I did when I saw the documentary Eyes on the Prize in middle school. At that point, it just took off for me. I began reading everything I possibly could, watching every documentary I could because I was growing up in a predominantly white school and I was treated really poorly by the other students.

That research helped me start to put together the pieces of structural racism, and how that impacted my entire existence.

On a more futuristic note, my dad is a huge music head. He loves blues, funk, soul, rock—real Black roots music. He was very into Sun Ra when I was a kid; I remember watching a few recorded live concerts. I would ask my dad, "Wait a minute, so you are also into this dude that wore outer space outfits with giant headpieces, and he’s different than the Parliament mothership?" In our home growing up, there was also a lot of James Brown and Tina Turner and other very specific Black and proud identity pieces that were a big part of my artistic evolution.

There is also the component of how all of this fits into my Jewish side. It’s connected but different at the same time: struggling with the legacy of trauma and outsiderness; the difficulty of forced diasporas, but having a lot of those stories documented and still told, so much so that we, Jewish people, have multiple holidays and opportunities of observance per year. We can really think about these issues, talk about it, put it out in the open, still feel the pain and the difficulty and the struggle from it, but it is really different for Black people in America. I was always interested in that juxtaposition, and that my two parents could connect on the trauma, and truly heal in their union.

LaFrae: That's really interesting. I was thinking as you were speaking about how I was always connected to futuristic things, but I didn't really make the connection right away. Also being queer—the Christian religion also told me that I didn't have a right to exist. However, I love spiritual and gospel music, not because of the message of Jesus, but because of the way those sounds allow one to heal and transport through sound, to travel to new areas, open up new portals. To this day, I love and listen to that music.

Leah King, Oakland garden, Mixed media (paper, glitter), 2021

Leah King, Oakland garden, Mixed media (paper, glitter), 2021

Leah: Totally. To me, some of the earliest American Black futurism is in the spirituals. Many spirituals are about envisioning an alternative reality, a different place, where we are living in our alternative future, our alternative now. Robin D.G. Kelley's book, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, talks about the psychosocial liberatory power of spirituals. If we are dealing with so much subjugation and can mentally put ourselves in a place where we're already interpreting freedom within our body, everything oppressive that happens outside of it doesn't actually matter.

This notion of alternative, liberated reality is similar to the ideas you can find in Octavia Butler’s books. I thought that was fascinating, the connection between Black spirituals and science fiction. I explored a lot of that in the very early days of college. Then I joined a gospel choir my freshman year, which really tripped me out because more than half of the choir was Jewish. [laughter] What is that about? It was all “Oh My Savior Jesus, yes Jesus” and everyone's just singing along. I thought, “Are we allowed to sing this??” [laughter] There's definitely a connection there, but I've put a lot of gospel, a lot of spirituals into my music over the years. It's been incredibly healing, as you were saying. Gospel has been so important for finding a deeper, specific connection to how my body and music connects to my healing process.

LaFrae: As I got older and started studying, it was the Civil Rights era, the protest movement manifested through expressions in the Jazz community, that really got me started as a musician. That era—the hard bop, post-bebop of the late fifties—is what really inspired me, the different types of expression, which are very Afrofuturistic.

In so many places like in the Georgia Sea Islands, parts of African spiritual expressionism survived. I read accounts of collective ritual sound- and movement-making like in P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout, which is one of my favorite books. I was just talking about this book with someone backstage the other day—about the ring shout, about people sneaking out, going down by the water, taking a bucket, a large bowl or a wash tub and tilting it ever so, to help catch the sound as they performed an ecstatic, traditional walking in a circle, holding sounds for healing by the light of the moon.

Leah: I wonder where the ring shout is today. How has it evolved? How do we do it in New York or San Francisco? What is our modern ring shout? I'm so dedicated to dance music. House music is a big part of how I perform ritual.

LaFrae: I think the ring shout probably exists in techno, which I found through Drexciya. That's when I discovered that Afrofuturism was a thing. Drexciya is an electronic music duo. They were at the birth of techno in Detroit in the 80s. Their mythos was about the enslaved Africans that were thrown overboard or jumped off ships during the Middle Passage; how they birthed the race of the Drexciyan, a nation of people who could breathe and thrive underwater. Drexciya made eight albums that told the story of these people. The musicians, James Stinson and Gerald Donald, were so committed to their ethos. They kept their identities anonymous for a long time and every time they put out a new record, say, in 1994, they would list the release date as 1612 or something.

Leah: I always knew the Drexciyan story, but I don't know if I've put together that it was also an electronic music duo from Detroit.

LaFrae: Really, the birth of techno. Techno being Black, I don't have to tell you.

Leah: I was thinking about the visual of the ring shout, of people having the drums tilted to the side and moving around and I started thinking of DJs and DJ aesthetic and all of us—the audience—centering around the DJ, staring at the DJ, pointing to the DJ; everyone having that very spiritual experience with house music and being at the club. I’ve missed that so much during the pandemic. That transcendental experience has always been one of my religions. When I get confused as to what I'm doing, I remind myself of the time in 2011 at Panorama Bar in Berlin, when I looked up into the ceiling and I thought, “This is it. This is where I'm supposed to be. I'm supposed to be listening to deep house music with a group of people. Everyone's sweating and we're letting our cares, our emotions, our worries, our joy, our pain, the sunshine, the rain, we're letting it all go together. This is where I need to be.” There’s a particular passage in James Baldwin’s Go Tell it On the Mountain about a preacher who gets everybody to that heightened place during a service. I was so engrossed with it—this moment of sweat on the brow, the transportation, the spectacle of it all. I thought, “I want to do that!” I want that release which seems so unrelated to what I know of as religious practice—either in synagogue or when I’ve been to church. In my adult life, that true sense of personal and spiritual release has always come from what is considered secular music.

LaFrae: I also think that the original blues captured that feeling and that it’s been parsed out into other genres: a little piece in rock ‘n’ roll, a little piece in country. Little pieces of it are living in all music. Blues is the roots and everything else is the fruits.

Leah: It's funny you say that. In Rock Camp last week, the guitar teacher, who is a good friend of mine, was teaching her students the twelve-bar blues. The first afternoon in band practice, a student who had never played guitar before just started ripping on that twelve-bar blues and I said “Wow, is that what you learned today?” and they replied, "Oh, I don't really know, it's just coming out of me."

LaFrae: Yeah, I concur. I did music for a theater presentation about mathematician and astronomer Benjamin Banneker, whose mother was enslaved. Banneker built clocks. He was an observer, a self-taught scientist and interestingly enough, from his meticulous logs, figured out the existence of Sirius B before NASA officially identified it. Benjamin Banneker's grandfather was a descendant of the Dogon people in Mali, West Africa. There is a hypothesis—noted in Robert K. G. Temple’s book, The Sirius Mystery—about how the Dogon people preserve a tradition of contact with intelligent extraterrestrial beings from the Sirius star system.

Interestingly enough, very much like Tesla, when Banneker died, his cabin with all his work and writings mysteriously burned down, within a few days of his death.

Leah: Hmm. Okay. I'm going to show you something that's really tripping me out right now. I keep this next to my desk. It's a clock—

LaFrae: That Benjamin Banneker made?

Leah: Well, it’s an art piece of Big Ben, and it’s made out of gear pieces from a wristwatch. I don’t think I ever realized that Benjamin Banneker was a clockmaker. Even though Big Ben is named after someone else, this one will now be named after Banneker.

LaFrae: We futuristic in ways we don't even realize.

Leah: We are!

LaFrae: Well, let's talk about your work. First of all, I love the way you've taken the older photos, the photos that seemed to talk about the past, and created images that are futuristic. I love that.

Leah King, Deep House (work-in-progress), 2021

Leah King, Deep House (work-in-progress), 2021

Leah: Thanks. It's about reframing histories and continuing the lineage of storytelling. How can I tell more stories? The next piece that I'm still batting around in my head, well, not batting—evolving in my mind—is the one with the cabin, the actual cabin in Gaithersburg, Maryland, where my relatives lived when they were enslaved in the 1800s. It’s just been really heavy. I stopped working on it and I'm going to start again tomorrow. I can't quite figure out what it's supposed to be, other than a deep house. Maybe I'll call it that—“Deep House.” I’ve been wanting to take this plantation cabin and just reframe it as a place in which one of my relatives is just in there, dancing all the time.

What if this is the place where—I keep calling it the Studio-54 cabin—what if it's where my relatives found their release? Or I can reframe it for myself as a place where they were valued and beautiful and covered in glitter and shimmer and shine and had the capacity for all the things they wanted to be. What if I'm able to turn my memories about them, the memories I don't even know that I have, into that? Then I can jump off of that story rather than a story of a white family still living on that property in Maryland and benefiting from my family’s labor.

LaFrae: I once showed you my family had a cabin, similar kind of wood and build to yours. I think I showed you my aunt and my grandmother climbing on it.

They were pre-teens in that photograph. Almost anything that was built by hand, my grandfather's hands, my uncle's hands, my aunt's hands, I saw my elders hold that dearly. There was value in process and understanding process, which I don't think people today take the time to really think about.

Leah: Right, and if we think of their opportunities for creative expression in that time. I mean, my grandparents on my father's side were both hardcore artists, but neither of them pursued arts careers. My grandfather was a Tuskegee airman, a twenty-seven-year military vet who flew in WWII and had a very illustrious career in the military. My grandmother was a tailor who went to Pratt Institute for a period of time. She could sew anything, create anything, do anything with her hands. I think that's true for a lot of women of that generation. I have a leather jacket that she made here in my studio and I've got stuff that she made all over the house, blankets and whatnot. My grandfather in his later years started writing poetry and was always talking about literature and music.

I've always wondered how different the arts would be in my family if we'd had a different connection to them. A lot of what families do is out of necessity rather than out of preference.

I wonder where we’re going next with some of our work. What do you think? I guess it's a funny question to ask because we've always been here, unearthing what already exists and maybe putting a different little shine on it. We're all sharing these stories together. I hope this is what we can continue to do.

Courtesy Willie Mae Rock Camp/LaFrae Sci

Courtesy Willie Mae Rock Camp/LaFrae Sci

LaFrae: My exploration into futurism has allowed me to put things into place, put things to rest, and to kind of make sense out of them. I feel an obligation to pass that on, which is why the futurism work with young people feels like a priority. For me, that’s really what's next. Of course, I'm going to be doing my thing, playing some drums, making some music, but futurism feels like my real calling right now. How about you?

Leah: Well, I'm really interested in the business of art and all the ways that I can be a part of claiming reparations, and bringing wealth back to my community. That's why I'm pursuing art and business at the same time by taking Business Leadership classes at Berkeley right now. We'll see where it goes from there, but I'm ready to have some more wealth-building in our community.

LaFrae: I hear that. Go on with your bad self, we'll meet you in the middle.