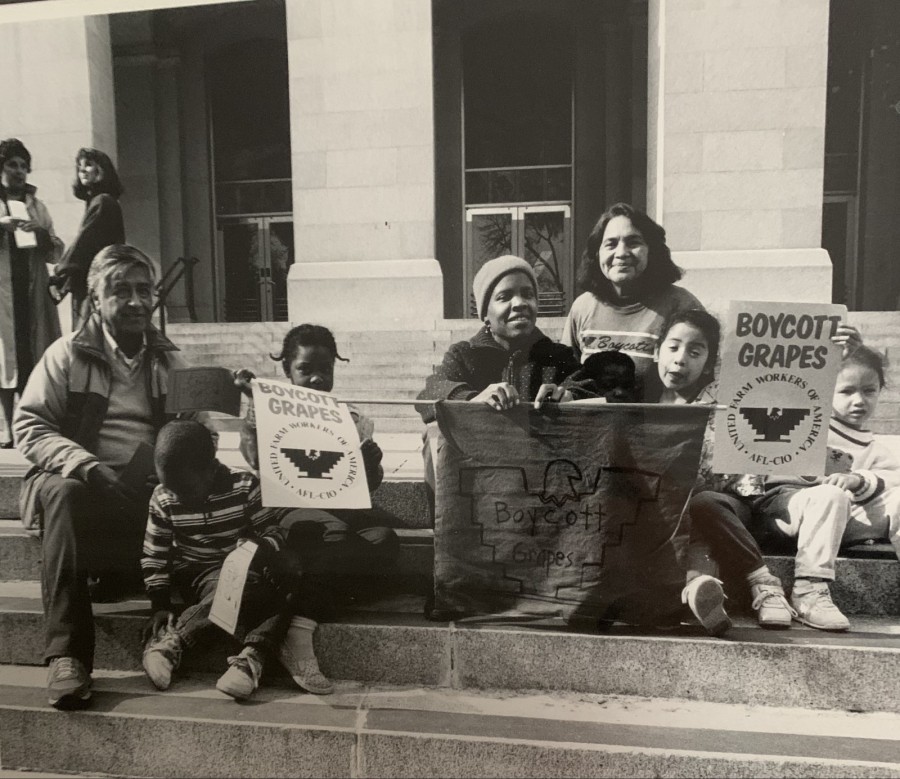

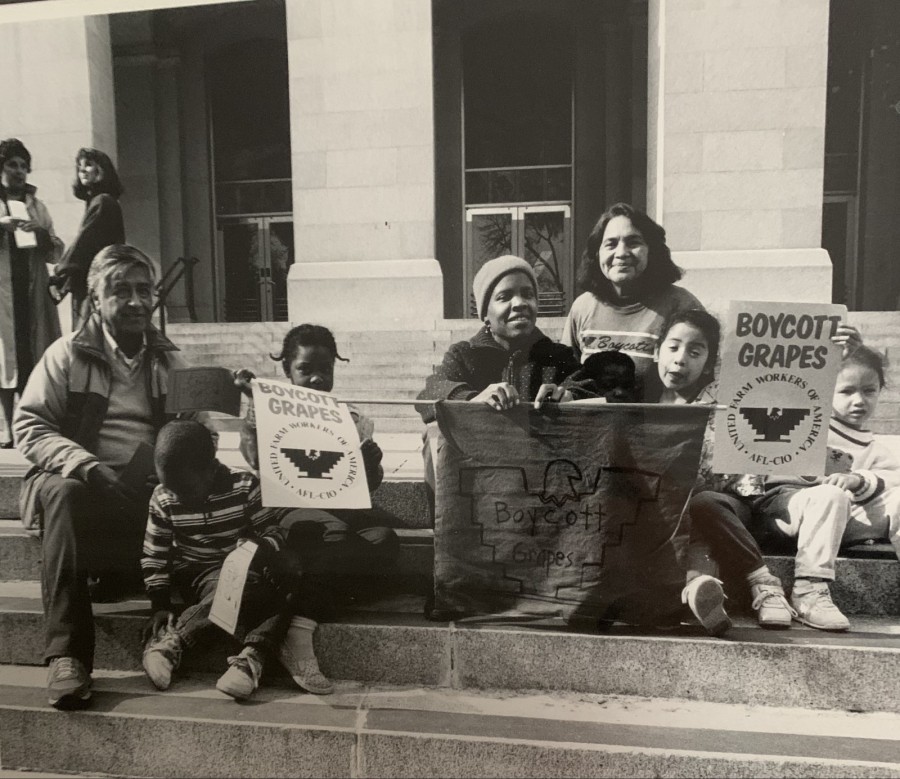

Qianjin Montoya (second from right, bottom) with César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and friends sitting on the steps of the California Capital in Sacramento, ca. 1991. Photo: Francisco Dominguez

Our kitchen smelled of savory, simmering food, hot coffee, and a hint of wet cardboard. Every burner on the stove was fired, the coffee maker was bubbling over, and friends and neighbors carried in boxes filled with dishes, leaning in for hugs, greeting us and apologizing for tracking their wet shoes in the house. I listened as adults reminded me and the other children (there were always so many of us!) to stay out of the kitchen unless we wanted dish duty, and to be mindful of the adults talking in the living room—many of them had come from very far away, and tomorrow would be a long day.

These gatherings always included people I’d never met before, but even the strangers felt familiar. The men with brown, sun-creased faces reminded me of my great-uncles, who had worked as farm workers their whole lives. Many of the younger folks spoke Spanglish to each other and Spanish to the elders, like we did, a family of native Spanish speakers born and educated in the United States. I noticed how women wrapped their chubby-cheeked babies in rebozos like my mom had often done with my nephew. While the smell of food wafted throughout, the house buzzed with dialogue and debate, greetings and embraces punctuating the talk of preparation and strategy. It was electric and as natural to me as the sound of my mother’s voice as she called for me and my brother to bring up extra chairs from the basement.

Qianjin Montoya (second from right, bottom) with César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and friends sitting on the steps of the California Capital in Sacramento, ca. 1991. Photo: Francisco Dominguez

César Chávez was a dear family friend. He would often call ahead (sometimes far in advance, other times just before arriving) to let my parents know that a group from the United Farm Workers (UFW) was coming to our house in Sacramento. On this night, the UFW gathered to discuss a protest at the California State Capitol the next day.

Founded by César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and other labor and community organizers in 1962, the UFW fought to establish and protect the working and human rights of farm laborers and their families against growers and large agribusiness corporations. Migrant farm workers in the U.S. have historically suffered from discrimination and poverty at the hands of profit-prioritizing businesses. Social unionizing in the U.S., specifically in support of non-English speaking, impoverished, immigrant workers, began in the mid-nineteenth century and is part of a distinctly Jewish-American tradition in industrial relations. This history and Jewish shared values of social justice and impetus to organize for widespread change were an integral part of César’s education when founding the UFW. César was known to study the work of many Jewish social unions and their leaders—David Dubinsky of the Ladies Garment Workers Union and Ralph Helstein of the United Packinghouse Workers of America were among his predecessors and collaborators. And many of the UFW’s critical organizational skills and resources were gleaned from modern Jewish community organizers such as Fred Ross and his mentor, Saul Alinsky, with whom César had worked at the Community Service Organization for over ten years. Through community organizing and campaigns seeking justice for day laborers, the UFW gained supporters across diverse geographical, cultural, racial, and class lines and fueled a powerful civil rights movement that still fights against the growers and legislators who continue to exploit farm workers today.

César Chávez speaking at a UFW rally on the steps of the California State Capitol in Sacramento (detail), 1971. Photo: Hector Gonzalez

The energy to organize and mobilize fueled much of my childhood in the late 1980s and early 1990s— I was born into a family of activists, but I didn’t learn to name our work that way until later. Growing up I thought everyone knew about grape boycotts and about never crossing a picket line. Like César, my family’s commitment to social justice and civil rights was something they learned from those before them and taught to those after; my siblings and I were all raised in community organizing and still consider it a pillar of our lives and work. While poster-making had been a major part of our participation, my family joined many other activists in support of the UFW through marches, fundraisers, community gatherings, and boycotts.

Qianjin Montoya on a picket line in front of a Safeway in Sacramento, CA with her parents, Juanita and Jose Montoya, ca. 1989. Photo courtesy the Montoya family

César passed away in 1993 when I was nine years old. Attending his funeral and the march that followed is the last memory I have of him. I remember the heat in Delano that day and what felt like an endless sea of people who had gathered to say goodbye. But what so many of us were also engaged in, that day in April, was recommitting to honor and continue his work. The circumstances that made César’s life’s work necessary are still present almost thirty years after his death, and the need to organize against oppressive systems of government and exploitative structures of labor persists seventy years after he worked to do so with Ross and Alinsky. But these forces are met by the multitudes who continue to doggedly support the struggle for social justice and civil and human rights.

Qianjin Montoya (front, center) with her mother, Juanita Montoya (top center) and her godparents, activist and musicians Patricia Wells Solorzano (left) and Agustín Lira (right) at the California State Capitol in Sacramento in 1994 at the culmination of the march from Delano to Sacramento on the one-year anniversary of Chávez’s death. Photo courtesy the Montoya family

I was raised in the noisy, hectic environment of activist organizing. I am proud to bring these experiences and values to my work at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, and prouder still that the institution I am a part of has those same values embedded in its cultural history and vision for the future. Today, the stakes are still high and the urgency to work together across industries, borders, and any other defining lines still feels complex and messy at times. But all of the movement and all of the noise in the gathering to organize is imperative, because it is a critical way to show up and to make clear: tonight we’ll gather, tomorrow we'll march—together.

Qianjin Montoya is assistant curator at The CJM. Her practice includes curating, writing, and research, with a focus on institutional histories and the narratives of women and people of color. Her curatorial research has been featured in exhibitions at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (San Francisco) and in programming at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. She recently completed work as the Americas Collection Research Fellow at Kadist in San Francisco. Montoya holds a Master of Arts in Curatorial Practice from California College of the Arts, and a Bachelor of Arts in Art History from the University of California, Berkeley.

Header image: César Chávez speaking at a UFW rally on the steps of the California State Capitol in Sacramento, 1971. Photo: Hector Gonzalez