Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

This resource guide is intended for educators or anyone interested in exploring ideas related to art, resilience, history, or the Holocaust. The guide explores the impact of the past on the present, highlights examples of resilience, takes an in-depth look at architect Daniel Libeskind’s life, and examines ways visual artists have used art to express ideas about resilience. Designed for high school students, this document is a companion to the tour Resilience, Holocaust, and the Architecture of Life and may be used before or after a visit to The CJM, or as a stand-alone resource for teaching.

Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

How do we move forward from the pain of the past while vowing to never forget? The architecture of The Contemporary Jewish Museum (The CJM) is a testament to resilience and a dialogue between past and present. It is a celebration of life and strength designed by architect Daniel Libeskind, a child of Holocaust survivors, with deeply embedded Jewish symbolism and meaning. In this discussion-based program, participants will explore the symbols of The CJM architecture; discuss the relationship between past and present; learn about architect Daniel Libeskind; hear from a Holocaust survivor; and create their symbolic structures.

Resilience and the lessons of the past for the present day are key messages in the Resilience, Holocaust and the Architecture of Life program. Consider having students read some or all of the following resources to help center the conversation:

Discuss these questions to gain a stronger understanding of resilience. This can be facilitated as a large group or in multiple small groups.

Daniel Libeskind. Photo by Kira Sugarman.

In this short activity, participants learn about some of Daniel Libeskind’s symbolic buildings, then will break into pairs or small groups and focus on a time period in Daniel Libeskind’s life, discussing how Libeskind himself moved from oppression to creativity—creating buildings that link past to present. After reading the biographical information, each group will create one symbol and one word that summarizes the information and be asked to explain this to the group. Allow 5–10 minutes for discussion and 1 minute each for the groups to report out.

Daniel Libeskind’s Biography

Libeskind Interview on Childhood Bullies, Nazi Germany, and Jewish Museums

Daniel Libeskind on Architecture and Memorials

Introduce students to one or two of Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish museum buildings, looking at structure, symbolism, and meaning for each.

Then, break class into small groups (depending on the group size—groups should be 5 or less, some may have duplicate information) to learn more about Libeskind’s background.

She had to sew white silk shirts for officers. The only way to protect against frostbite was to wrap newspapers around her feet.

I used to walk to school, or with my father to the Jewish cemetery—the biggest Jewish cemetery in Europe—trying to interview anyone who was Jewish and had survived. I held my father’s hand as he went up to people and asked, like a code, ‘Are you of the people?’ and broke into Yiddish. But there was no one left.

The grimness. Coupled with a sense that the Holocaust was not over. At school, my name alone was enough. The other boys used to hit me. I’d run back home not to get hit. I was always in flight.

I arrived by ship to New York as a teenager, an immigrant, and like millions of others before me, my first sight was the Statue of Liberty and the amazing skyline of Manhattan. I have never forgotten that sight or what it stands for.

Daniel Libeskind. Photo by Kira Sugarman.

He comes over to me, puts a finger to my chest and says aggressively, determined to fire me, ‘What buildings did you do in the past, Mr. Libeskind, to qualify you to do this?’ I said: ‘If you go by the past, Berlin is not going to have any future.’

I told him, ‘I haven’t come to Berlin to build office buildings. I came here to build the Jewish Museum,' and I walked out, slamming the door.

Just as Daniel Libeskind used architecture to process and communicate messages about the past to the present day, artists often use their art as a tool for processing traumatic events, or linking past, present, and future.

Watch this short (three minute) video Colours of Resilience: Street Art with Syrian and Jordanian Youth Across North Jordan, which shows displaced people making a mural in a refugee camp. Then discuss the questions.

Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

Throughout time, artists and ordinary citizens have created art to protest, critique, or resist the dominant culture. This art has taken many forms—often painting and sculpture, but also graffiti art, murals, performances, and music. Protest art also marked a shift in who created art—from the domain of artist to also include social activists and ordinary citizens with a message to convey. Activist art seeks to reach a wide audience, and for this reason generally is created and displayed outside of a museum or gallery setting.

One of the best-known early examples of protest art is Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica. Often called modern art’s “most powerful anti-war statement,” Guernica was created for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair, and was Picasso’s response to the bombing of Guernica, a small town in the Basque region of Spain, by Germany at the request of the Spanish nationalist government. During this attack, 1600 civilians were killed or wounded. The mural (originally displayed near a monument to Nazi Germany) depicts the suffering of humans and animals, but Picasso refused to interpret the symbols for his viewers, stating,

It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words! The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.

This activity invites students to look at and interpret the symbols in artwork related to resilience. Print and post the works of art on the following pages in different places around the classroom, providing the included contextual information. Divide the students into small groups and have them discuss each piece of art and then rotate until they’ve seen them all. Have a short discussion as a class to debrief the experience.

Installation shot of Amelia Falling with visitors, in From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art, on view November 25, 2016–April 2, 2017 at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

(b. 1976, Plainfield New Jersey; based in New York)

Thomas’ work focuses on the representation of race, gender, and ethnicity, notably incorporating elements from advertising, pop culture, and entertainment. Most of his installation and photography works deal with the struggles that African Americans have faced for decades, before and after the Civil Rights movement’s peak in 1968. Amelia Falling is derived from a Spider Martin photograph of Amelia Boynton during the Selma March in 1965. Thomas is concerned with mental and visual aspects of concealment and revelation in relation to how the meaning of historical moments evolves over time. The work, a mirror created through a rare custom silvering process and printing, leaves certain sections transparent and reflective, freeing the viewers to see themselves within the image.

Hank Willis Thomas, Amelia Falling, 2014. From Generation to Generation: Inherited Memory and Contemporary Art. On view November 25, 2016–April 2, 2017, The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

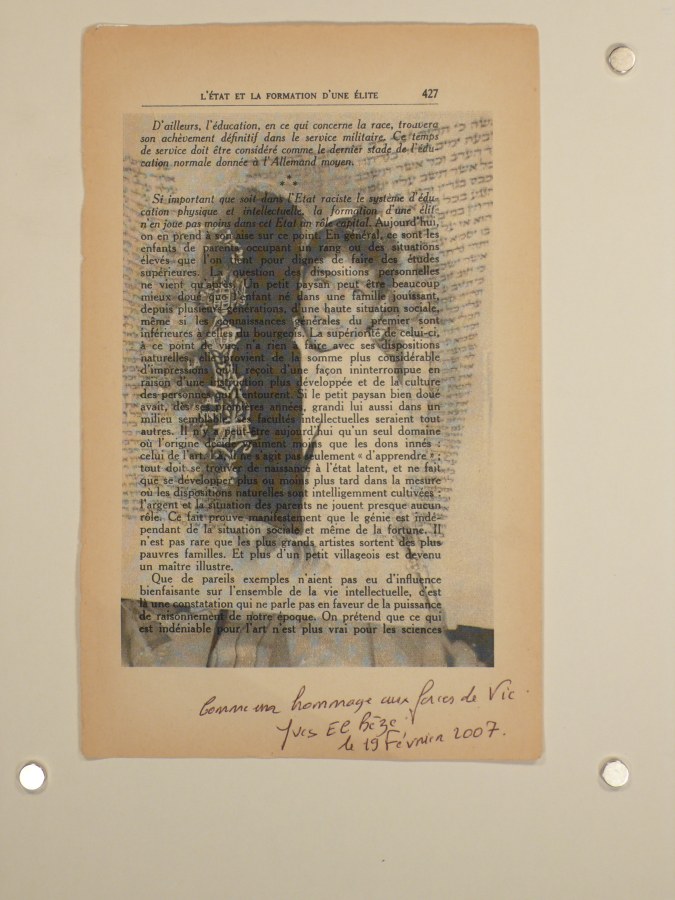

Yves El Bèze. From the project Notre Combat by Linda Ellia; one of 600 works on paper; 8 ¾ x 5 ½ inches; Paris, France; 2007. Courtesy of The Contemporary Jewish Museum.

(Born in Tunisa; based in Paris)

In 2005, French painter and photographer Linda Ellia’s daughter showed her a book she had come across at the home of a family friend–a French translation of Hitler’s notorious memoir and manifesto Mein Kampf (My Struggle). Ellia, who is Jewish, was stunned as she held the thick tome. It was as if she was holding Hitler in her hands, and the book’s weight was the heaviness of the Holocaust. She felt immediately compelled to respond. She awoke one night with an idea—what if she detached one of the pages to express her anger and resist the book’s horror? Grabbing a large red marker, she drew the head of a woman screaming on the loose page and named her Aile (the French word for ‘wing’).

Over the next three years, Ellia distributed the pages of Mein Kampf one by one to individuals from all walks of life—professional artists, youth, and ordinary citizens each invited to paint, draw, sculpt, collage, and blacken the page however they wished as a reaction to the text and its themes. Six hundred pages came back to her and she gathered the results into a collective artwork and book titled Notre Combat (Our Struggle) published in 2007 by Seuil Editions, a leading publisher of art books in France.

The following text was included by the creator of the image of a boy holding a Torah, and may be used to supplement the questions.

…I long had a nauseous feeling that kept me from responding to the offer being made. A haunting mystery paralyzed me: how could a people at the height of its civilization be lead down the path of barbaric devastation simply by reading these terrible, yes, but mostly pathetic words?

At my son Nathan’s bar mitzvah, I finally saw the light and no longer felt paralyzed when I saw his beaming, joyful face. A face that would have purely been that of an angel had it not been for the fact that his grandfather survived Nazi hell. It is by measuring out my emotion as a father witnessing his son’s coming of age, an emotion I had felt from my own father, who must have also felt it from his father, that I figured that the best way to send these foul lines back to hell was to cover them with these sublime Hebrew texts and with the smile of a little Jew radiating life.What a wonderful idea you’ve had to turn this message of hate into a message of love!

Miranda Bergman and O’Brien Thiele, The Culture Contains the Seed of Resistance (detail), 1984. Painted in Balmy Alley, San Francisco Mission District. Photo by Cipster.

(b. 1947, Oakland, CA and b. 1941, Berkeley, CA)

This mural, painted in 1984 in San Francisco’s Mission District, shares diverse images of Central American life, from violence and war to music and culture. Originally painted during wartime in Central America, it was designed to call attention to war, oppose US intervention, and to cultivate respect for and solidarity with Central American people.

Miranda Bergman and O’Brien Thiele, The Culture Contains the Seed of Resistance, 1984. Painted in Balmy Alley, San Francisco Mission District. Photo by Cipster.

Photo by Gary Sexton Photography.

Wrap up the discussion on resilience with these questions and then a short exercise. After the concluding thoughts or questions (if the group has visited or plans to visit The CJM), hand out post-its and ask students to write down a sentence about what they learned and/or the main message they think is important from this workshop. Have students do a pair-share with a classmate sitting near them. Post the answers up in front of the class and ask for a few people to share with the group.

For more information about Resilience, Holocaust, and the Architecture of Life, or to book a tour, please call us at 415.655.7857 or email tours@thecjm.org. Learn more at thecjm.org/tours.

School and Teacher Programs are made possible by Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Leadership support comes from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and The Lisa and John Pritzker Family Fund. Patron support is provided by the The Bavar Family Foundation. Additional generous support is provided by the Robert & Toni Bader Charitable Foundation, the Mimi and Peter Haas Fund, the Toole Family Charitable Foundation, and the Ullendorff Memorial Foundation.