Image credit: Dachau Badges Poster. Image courtesy of USHMM via Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.http://hmd.org.uk/page/badge-system-0

In conjunction with the exhibition Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show, on Friday April 21, San-Francisco-based maggid (sacred storyteller) and author Andrew Ramer presents a lunchtime Gallery Chat from 12:30–1pm on the subject of the Pink Triangle. The chat is presented in partnership with Congregation Sha’ar Zahav. Ramer’s work is grounded in narratives from parallel realities. He is the author of Torah: Told Different: Stories for a Pan/Poly/Post-Denominational Era; Queering the Text: Biblical, Medieval, and Modern Jewish Stories; and Two Flutes Playing, which has been called a “gay underground classic.” Ramer is also the world’s first ordained interfaith maggid and is a longtime member of Congregation Sh’ar Zahav. In this blog entry, Ramer and CJM Associate Curator Anastasia James discuss two instances of the Pink Triangle as memorial in San Francisco: The San Francisco Pink Triangle, an annual installation on Twin Peaks, and Pink Triangle Park, a permanent memorial in The Castro.

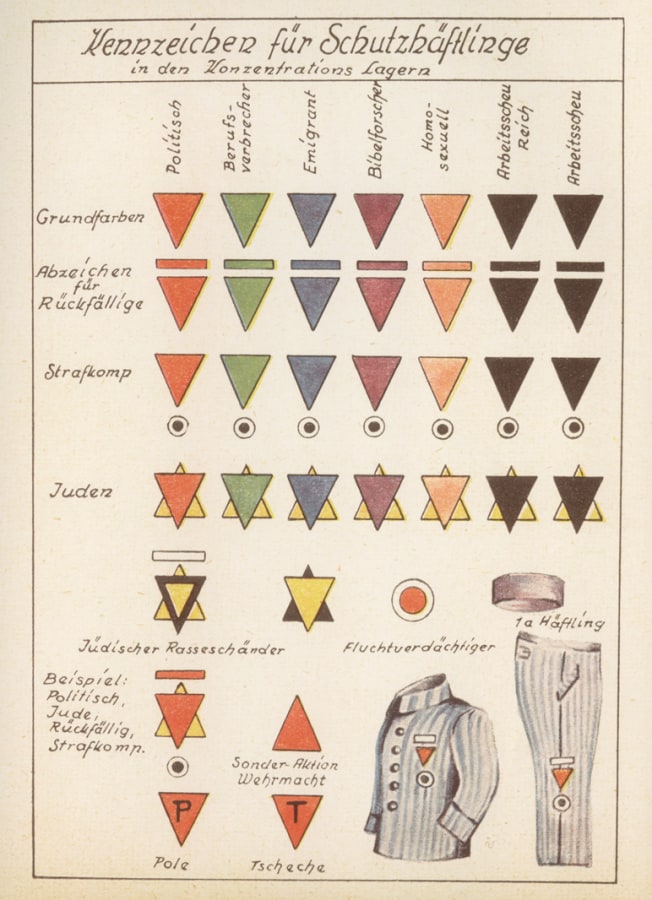

For efficiency in persecution, badges—primarily triangles—were part of the system of identification1 employed by the Nazis in concentration camps to demarcate the reason for the prisoners’ placement. These mandatory badges of shame, which were made of fabric and sewn onto both the jackets and trousers of the prisoners, had specific meaning indicated by their color and shape.2 The system of badges varied between the camps. The following coding system was used before and during the early stages of World War II in the Dachau concentration camp:

Image credit: Dachau Badges Poster. Image courtesy of USHMM via Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.http://hmd.org.uk/page/badge-system-0

If the single triangle badge was superimposed over a yellow triangle (forming a six-pointed star), this indicated that the prisoner was of Jewish faith. In addition to the color-coded badges, some groups had letter insignias on their triangles to denote country of origin, and there were many different markings and combinations.

Many postwar memorials to the victims of the Nazis utilize triangle motifs in direct reference to the identification patches used in the camps. Typically, an inverted triangle (point down, base up) is used to invoke all victims, including non-Jewish victims, as is the case with the use of the inverted Pink Triangle. In 1972, Hans Neumann (under the pen name Heinz Heger), published a biography of his acquaintance Josef Kohout titled, Die Manner mit dem rosa Winkel (The Men With the Pink Triangle). This book was the first testimony from a gay survivor of the concentration camps to be translated into English. Many credit this book for drawing attention to the symbol of the Pink Triangle and perhaps inspiring the adoption of the Pink Triangle, turned upwards rather than inverted, as a pro-gay symbol by activists in the United States during the 1970s.

In 1986, Richard Plant, a gay Jewish author who fled Germany in 1933, published The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals, which shed further light and drew attention to the symbol.

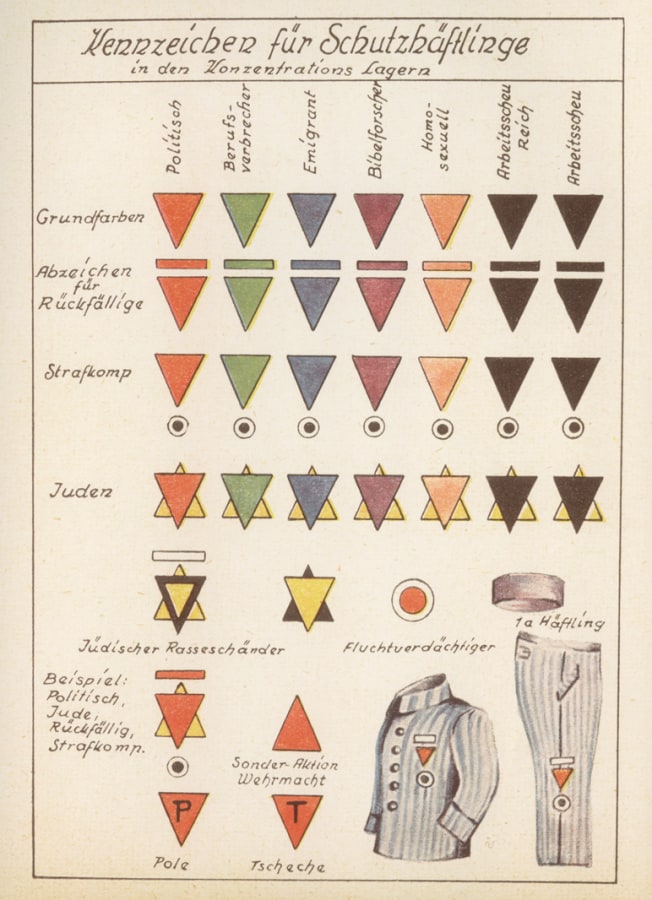

In 1987, six New York gay activists (Avram Finklestein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Lione, and Jorge Soccaras) formed the Silence = Death Project and produced posters featuring a prominently placed pink triangle on a black background with the text “SILENCE=DEATH.” In its original manifesto, the project drew parallels between the Nazi period and the AIDS crisis, stating that, “silence about the oppression and annihilation of gay people, then and now, must be broken as a matter of our survival.”4 The six men later joined the activist group ACT UP and offered the logo to the group.

Image credit: ACT UP Poster. Public Domain.

Since 1996, the image of the pink triangle has been used annually in San Francisco by a group called The Friends of the Pink Triangle during SF Pride weekend. This group installs, on the north facing hill of Twin Peaks, a memorial consisting of an acre-sized pink triangle comprised of 175 pieces of pink canvas, held in place by steel spikes. According to the organizing group’s website thepinktriangle.com, “The Pink Triangle of San Francisco is an annual commemoration of the gay victims who were persecuted and killed in concentration camps in Nazi Germany starting in 1933 through the end of WWII.”5 The organizers view The Pink Triangle of San Francisco as, “an educational tool for all to see,” and share that the organization’s goal is to, “educate people about the hatred of the past to help prevent it from happening again.” Given its enormous size and its positioning facing the Castro and Downtown, on a clear day, it can be seen for twenty miles and is an important reminder for the LGBTQ community of the continuing homophobia and inhumanity against them and other repressed minorities around the world.

Pink Triangle on Twin Peaks, [June 2006]. Photo by Daniel Nicoletta from a helicopter.

The organization behind The San Francisco Pink Triangle was founded by Patrick Carney, Thomas Tremblay, and Michael Brown. Carney continues to organize the installation and commemoration ceremony each year with the ongoing support of his husband Hossein Carney, his sister Colleen Hodgkins, and their 93-year-old mother Edith Carney, who hands out donuts and coffee to all the volunteers.

This year’s installation will take place on Saturday June 24, 2017 from 7am to 10:30am—come early! Bring a hammer, work gloves, sunscreen, and closed toe shoes. Dress for both warm and cold weather. There may be poison oak. The commemoration ceremony will take place at 10:30am.

You can click here for the Twin Peaks Pink Triangle’s history and to volunteer to help set it up and take it down for Pride Week in June:

A less well-known related memorial is the Pink Triangle Park, a triangular shaped 3000 square foot mini-park located at the intersection of 17th Street and Market Street, directly above the Castro Street Station of the Muni Metro. The idea for the park was conceived in 2001 by Joe Foster, a resident of the area who according to a San Francisco Chronicle article, was inspired by an exhibit created by the Gay Museum of Berlin, called, Persecution of Homosexuals in Nazi Germany, 1933–1945, and by the documentary Paragraph 175, produced by award-winning SF filmmakers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman.6 Ground was broken on the parks construction in December 2001 and was completed during the summer of 2002. It is the first permanent, free-standing memorial in America to the thousands of members of the LGBTQ community persecuted during the Holocaust. In the park, a fifteen-pylon sculpture created by Oakland-based artist Susan Martin and San Francisco-based artist Robert Bruce flanks a footpath at the park’s east end. Each pylon stands five feet tall and is composed of Sierra granite and is topped with an inset pink granite triangle. The landscaping of the park was overseen by Richard Sullivan, owner of Enchanting Planting, a SF-based landscaping business. The floor of the park is covered in Forest Floor Bark and the garden includes shrub roses, native California sages, blue oak grass, New Zealand flax, and Australian fuschia. The footpath is inset with a large triangle with small bits of pink quartz.7

Victor Klemper Book Club (Bear Witness), 2007/2016 is Cary Leibowitz’s homage to Victor Klemperer (1881–1960) a Romance languages scholar who became known for his journals published in Germany in 1995 which detailed his life under the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany, and the German Democratic Republic.8 The sections covering the period of the Third Reich, which provide unparalleled day-to-day accounts of life under tyranny, have become standard sources for scholars and historians. Two volumes, I Shall Bear Witness and To the Bitter End have been published in English translations. The work features a triangle-shaped wood panel painted yellow flocked by multiple identical ski hats emblazoned with the text, “Victor Klemperer Book Club” on one side and “Bear Witness” on the band and a Star of David on body of the hat. In this work, Leibowitz has appropriated the image of the uninverted yellow triangle. The yellow triangle was not one of the single-color triangles used to identify prisoners in concentration camps, but was used as an additional piece of identification. Sewn directly onto the uniform of the prisoner, it acted as an indicator of Jewish faith upon which an inverted triangle of a specific color (related to the color coded identification system employed by the Nazis) further identified the “crimes” of the individual.

For my bar mitzvah my mother gave me a mezuzah to wear around my neck. I was secretly happy a few days later when our beagle chewed it up. June of 1969, two weeks out of high school, the phone rang: an upstairs neighbor called to tell my stepmother that the fags had rioted the night before on Christopher Street. After breakfast she, my father, and I, walked over, but I could not bridge my hidden desire to the word “fag,” any other word, or to what had happened there the night before. I came out to myself three years later, alone in a movie theatre in Jerusalem, watching the film of D. H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love, and came out to the world a year after that, in Berkeley. In the time between Stonewall and moving back to New York in 1974, the world changed. There were words, names, stories, but very few images. In 1972 the book The Men With the Pink Triangle came out, the tale of a gay man’s hell under the Nazis, and that triangle, deliberately reversed from the Nazi badge to point upward, soon became a common image of gay liberation, seen on posters and signs held high at marches—but I refused to wear one, even though it helped me begin to link together my Jewishness and my gayness.

In 1981, AIDS appeared in our lives, and everything changed again. Another book, gay Jewish author Richard Plant’s The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals, published in 1986, further popularized the image. In 1987 the “Silence = Death Project” was formed in New York City, which used that triangle to tie Nazi persecution of gay men to the world’s silence about AIDS. The Project’s design was adopted by the activist group ACT UP and it spread around the world—but “Why,” I asked myself, “didn’t the black posters and buttons with their prominent pink triangle read: “Communication = Life”?—and I refused to wear one.

I was standing in someone’s living room, I think, when my partner at the time, the late Mark Honaker, handed me a button with one of Mark Venaglia’s spiraling triangles on it. The German for "Pink Triangle" is “Rosa Winkel,” which sounds like the name of a drag queen in a curly pink wig and fishnet stockings. It’s that vibrant playful Rosa-in-motion that Venaglia captured—and I immediately put on his button, the first such badge I’d ever worn, treasuring it—a sacred talisman that expressed the truth about myself and my tribe.

Mark Venaglia. “People Are Healing Themselves.” Image courtesy of the artist.

Then one sunny June day several years later, it was Pride Month again and I was marching up Fifth Avenue in Manhattan (or was it down?) when a wide-eyed young man half my age came up to me and said, pointing, “Where did you get that?” I knew that look—wonder, recognition, delicious delight—and having migrated from where I’d long worn it on my shirt to live down deep in my heart—I removed the button, pinned it to his shirt, and he danced off into the crowd, mirrored and happy. (And happy was I when The CJM invited me to talk and write about the Pink Triangle—and I found Mark Venaglia online, admired his beautiful work, and stepped back with him into a joyful conversation about how to live in this wobbly challenging time.)

Andrew Ramer is an ordained maggid (sacred storyteller) and the author of numerous books including Torah Told Different: Stories for a Pan/Post/Poly-Denominational Era, and Queering the Text: Biblical, Medieval, and Modern Jewish Stories. Some of his blessings and prayers can be found in the inclusive siddur from Congregation Sha’ar Zahav in San Francisco: shaarzahav.org/our-siddur/

Born in Queens, New York across the street from an amusement park named Fairyland, he now lives in Oakland, up the street from an amusement park named Fairyland, where he’s at work on a book about Serach, an immortal woman in Jewish folklore.

Anastasia James is the Associate Curator at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco and the curator of Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show and the editor of the accompanying catalog. Her research focuses on counterculture and the American avant-garde c. 1950–70 with particular emphasis on alternative practices. Anastasia is the co-editor of two book-length monographs: Billy Name: The Silver Age, photographs from Warhol’s Factory and Brigid Berlin: Polaroids published by Reel Art Press, London. Her recent exhibitions include: Brigid Berlin: It’s All About Me (Invisible-Export, 2016), Billy Name: The Silver Age (Milk Gallery, 2014), 13 Most Wanted: Andy Warhol and the 1964 NY World’s Fair (Queens Museum, 2014; The Andy Warhol Museum, 2015). James has worked for numerous institutions including The Andy Warhol Museum, The Carnegie Museum of Art, The Wurtembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart, and the Dia Foundation for the Arts as well as many single artist archives and private collections. She received her Master’s Degree from the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College.

1 revolvy.com/topic/Nazi%20concentration%20camp%20badge

2 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_concentration_camp_badge

3 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_concentration_camp_badge

4 actupny.org/reports/silencedeath.html

6 sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Park-honors-gay-lesbian-Holocaust-victims-2567573.php

7 sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Park-honors-gay-lesbian-Holocaust-victims-2567573.php

Andrew Ramer will talk about the Castro’s Pink Triangle at The Contemporary Jewish Museum on Friday, April 21, 2017. His talk is in conjunction with Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show and the commemoration of Yom HaShoah.

For more 36 Windows blog entries, click below.

Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show is organized by The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

Lead sponsorship is provided by Gaia Fund. Major sponsorship is provided by Dorothy R. Saxe and Wendy and Richard Yanowitch. Supporting sponsorship is provided by Pacific Heights Plastic Surgery. Additional support is provided by David Agger; Alvin Baum and Robert Holgate; and Michael T. Case and Mark G. Reisbaum.

The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibition program is supported by a grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Header image: Pink Triangle Commemoration Ceremony 2009. Featured in the photo are Cloris Leachman (in the chair); Academy Award-winning producer Bruce Cohen who made Milk, Silver Linings Playbook, and American Beauty; Academy Award-winning producer Howard Rosenman; many SF-elected officials; volunteers who helped install the pink triangle; and the SF Lesbian Gay Freedom Band. We are wearing pink triangles in solidarity with those who wore pink triangles in the concentration camps—we wore ours by choice whereas those in the camps obviously had no choice. Photo by Hossein Carney. Contributor bio: Andrew Ramer photo by Janet Sheard; Anastasia James photo by Gary Sexton Photography.